A pair of researchers from Duke and Chapman Universities wondered: Why did Western Europe become an economic juggernaut, while the Ottoman Empire steadily declined from its status as a superpower in the 1600s and 1700s?

The answer, it seems, may lie with the Ottomans’ lending system, according to their paper “The Financial Power of the Powerless: Socioeconomic Status and Interest Rates Under Partial Rule of Law.”

I spoke with Duke University’s Professor of Economics and Islamic Studies Timur Kuran and Chapman University’s Argyros School of Business and Economics Associate Professor Jared Rubin to better understand a credit market that appears completely foreign to modern-day consumers.

The reversal of fortunes

Kuran and Rubin focused their research on 17th- and 18th-century credit data from Istanbul, the capital city of the Ottoman Empire and the largest city of modern-day Turkey (however, Ankara became its capital in 1920.)

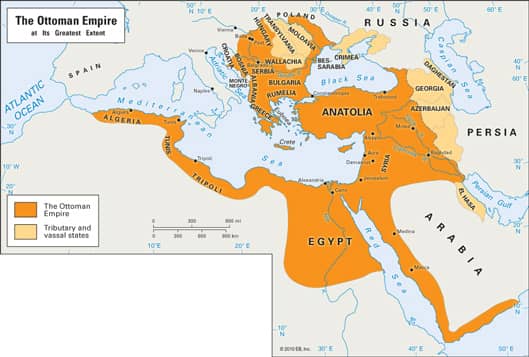

During this time, Istanbul served as the commercial center of the Eastern Mediterranean and had been one of the most powerful cities in the world at the time, servicing the extensive Ottoman Empire that sprawled across North Africa, the Middle East and parts of Eastern Europe.

The Ottoman Empire at its greatest extent, circa 1683-1699. Note that Istanbul was once known as Constantinople to the Western world. Why did Constantinople get the works? That’s nobody’s business but the Turks.

However, “its global importance is slipping,” Kuran said. “During this period, the Netherlands and England and Western Europe in general become increasingly important economically. The relative importance of Istanbul, as well as the eastern Mediterranean in general, is slipping.”

“This is a period, too, where both in England and the Netherlands in particular, credit markets are becoming much more complex,” Rubin added. “That’s being seen less so elsewhere, the Ottoman Empire being one of those places.”

The two decided to look at how the Ottomans’ credit markets may have contributed to the “reversal of fortunes,” as Kuran put it.

Why it paid to be poor in Istanbul

As modern-day consumers, we understand the importance of credit scores and how they factor into interest rates on loans — the higher your score, the more likely you are to pay back your debt and the lower your interest rate will be.

Vice versa, people with lower credit scores are less likely to pay debts, so lenders charge higher rates to get as much as they can before a possible default or bankruptcy. Our modern-day system works on the assumption if a lender takes a delinquent borrower to court, a judge will deliver an impartial verdict regardless of the borrower’s socioeconomic status or credit score.

However, as Kuran and Rubin found, impartiality was not the standard in Ottoman courts. Certain members of society — men, Muslims and elites — enjoyed a partiality in the court system, one that offered them greater protections from other less-privileged members of society.

“Whenever the judicial playing field is tilted sufficiently in favor of people of high socioeconomic status … they will pay more for credit.”

“It was easy to take them to court,” Kuran said. “But it was harder to collect from them on a loan even if they remained solvent. If they had the assets, if they had posted collateral for the loan and they refused to pay, it was harder to collect from them relative to collecting from a poor person or commoner.”

Because it was harder to win judgements against male Muslim elites, lenders charged members of this group higher interest rates (around 19 to 20 percent or more) because there was a risk they wouldn’t see their money returned — similar to our modern system, albeit with classes reversed.

Thus, because it was easier for lenders to win court battles against non-Muslim citizens, especially middle- to lower-class women, these groups enjoyed the lowest interest rates since lenders had the highest chance of seeing their money returned with interest.

“This proposition captures a striking relationship that is contrary to the connection between social class and credit cost observed in advanced modern societies,” Kuran and Rubin write. “Whenever the judicial playing field is tilted sufficiently in favor of people of high socioeconomic status, a competitive credit market will make them pay a price for the favoritism that they enjoy. In spite of their lower risk of default, they will pay more for credit.”

Lack of consumer protections

But couldn’t the poor non-Muslims just declare bankruptcy? Not in the Ottoman Empire.

“In the Ottoman context, you did not have bankruptcy laws,” Kuran said. “They could be sent to debtors court where they could work off the loans and wouldn’t be released until they paid off the loans.”

Likewise, if their homes were used as collateral, the courts “had no qualms” when it came to evicting them after a reneged debt, Kuran said.

“The one way you could really get away from paying your loan … is by leaving,” Rubin said. “Importantly it was way easier for men to leave than women because an unaccompanied woman would be very suspicious … this made it more likely a man would be able to escape his debts. Lenders made him pay a premium for his loans.”

As a result, males were typically charged a 3.6 percent more on their loans compared to their female counterparts, bringing their average premium to roughly 19 to 20 percent..

“In the Ottoman context, you did not have bankruptcy laws … the one way you could really get away from paying your loan is by leaving.”

However, elite Muslim men weren’t exactly known for reneging on debts.

“Most of them were good borrowers,” Kuran said. “If [defaulting on loans] was the standard practice, commoners wouldn’t lend to elites and elites wouldn’t lend to other elites, or they’d do so at astronomical prices.”

Rubin noted if delinquency was common, the typical loan for these privileged citizens would be much, much higher than the typical 15 to 20 percent.

However, “the poor people in 17th and 18th century Istanbul are paying less for loans than the poor in the United States today,” Kuran noted.

Certain modern-day payday lenders, they note, charge interest rates upward of 450 percent per annum.

Circumventing sharia law

Being a predominantly Muslim nation, Ottomans practiced Sharia law, the religious and moral code of Islam, to great extent. Those familiar with the code may wonder how lenders were able to charge and collect interest on loans when Sharia expressly forbids it.

Lenders and borrowers often agreed on an hiyal, or a fictitious purchase. For example, a lender would create a bill of sale for an imaginary item — a piece of cloth, a sword or perhaps an article of clothing — and the borrower would make payments on it.

In the case of a mortgage, both parties would agree on an istiglal, where the borrower used his or her house as collateral and paid “rent” to the lender.

“Well before the Ottomans, it was pretty easy to get around a lot of the basic rules against interest by fictitious sales,” Rubin said. “The spirit of the law was violated more or less from the first Islamic century on, especially in private loans.”

The takeaway

Why would the elite upper class, in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere, want to give up a financial court system tilted in their favor? If judges commonly ruled in their favor, why would they want to give up that partiality?

“The groups that stand to gain from a leveling of the judicial playing field with respect to financial contracts are not the powerless but the powerful,” they write. “Just as powerful states borrow more cheaply when political checks and balances make their promises more credible, so privileged groups make themselves more creditworthy when they force the judiciary to hold them to their financial contracts.”

“Privileged groups make themselves more creditworthy when they force the judiciary to hold them to their financial contracts.”

In other words, the creditworthy (who’re quite often also the wealthy) will pay less for their debts and loans because lenders know they stand a good chance at recovering unpaid debts. In short, impartial courts and bankruptcy laws actually make credit more accessible for the wealthy. Likewise, because poor/subprime borrowers have a bankruptcy option, their credit costs are much higher.

“The main lesson is that if, for any group, you make it difficult to collect on loans, that group will be hurt,” Kuran said. “Whether they’re privileged in other areas, whether they’re poor or rich. In designing financial markets and putting in place laws that regulate financial markets and loans, we should take into account the consequences of making it difficult to collect from one group or another. That’s the main takeaway that transcends the particular part of the world and period we’re looking at.”

Photo credit: gophoto.us, Encyclopedia Britannica

Advertiser Disclosure

BadCredit.org is a free online resource that offers valuable content and comparison services to users. To keep this resource 100% free for users, we receive advertising compensation from the financial products listed on this page. Along with key review factors, this compensation may impact how and where products appear on the page (including, for example, the order in which they appear). BadCredit.org does not include listings for all financial products.

Our Editorial Review Policy

Our site is committed to publishing independent, accurate content guided by strict editorial guidelines. Before articles and reviews are published on our site, they undergo a thorough review process performed by a team of independent editors and subject-matter experts to ensure the content’s accuracy, timeliness, and impartiality. Our editorial team is separate and independent of our site’s advertisers, and the opinions they express on our site are their own. To read more about our team members and their editorial backgrounds, please visit our site’s About page.