In a Nutshell: Earned wage access and cash advance loans appeal to workers who need financial flexibility to tide them over until their next paycheck. According to a recent Center for Responsible Lending analysis, these small-dollar, short-term loans carry costs and risks similar to payday lending products, including high interest, fees, and account overdrafts. The Center for Responsible Lending is a research and advocacy nonprofit dedicated to creating a fairer financial marketplace with opportunities for all families and individuals. This study reveals the expensive and counterproductive cycle that can arise when workers repeatedly use direct-to-consumer earned wage and cash advance products.

The number of Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck is increasing, with recent reports revealing that 60% or even 70% of consumers have no money left at the end of the month to save or invest.

Any unexpected expense risks sending these millions of consumers into a debt spiral, threatening their economic security and social stability.

Over the past decade, banks and fintechs have introduced innovative earned wage access (EWA) and cash advance products tied to employment and designed to provide a safety net.

Workers gain access to EWA through their employers as a benefit or through a direct-to-consumer model. They typically repay small cash advances on their next payday either directly from a bank account or as a payroll deduction.

If it sounds too good to be true, that’s because it is, according to recent research from the Center for Responsible Lending (CRL), a nonprofit dedicated to creating a fairer financial marketplace.

In “Not Free: The Large Hidden Costs of Small-Dollar Loans Made Through Cash Advance Apps,” published in April 2024, CRL probed EWA’s inner workings by analyzing data on millions of consumer transactions through a partnership with SaverLife, a nonprofit dedicated to using technology to improve financial health.

CRL matched more than 37,000 advances to nearly 2,000 unique users of direct-to-consumer EWAs and exposed the real-world financial consequences behind the promise of cash advance loans. The study found that EWAs were far from a panacea.

“Companies are advertising advance products as a way to protect against overdraft fees,” said Lucia Constantine, a Center for Responsible Lending researcher who worked on the “Not Free” project. “The most striking finding in our report is that consumers who used advances and experienced overdraft fees actually saw those fees increase, not decrease, after taking out an advance.”

Report Reveals Patterns in Millions of Transactions

The Center for Responsible Lending has a track record of more than two decades of consumer financial advocacy. The Center, which is affiliated with Self-Help Credit Union, one of the nation’s largest Community Development Financial Institutions, seeks to raise consumer awareness of potentially harmful financial products by producing research and undertaking advocacy campaigns to bolster regulations and consumer protections at the federal and state levels.

Federal and state policy teams perform advocacy work in Washington, D.C., and the states. Constantine’s team produces the analysis that informs the Center’s policy positions and advocacy campaigns.

To produce “Not Free,” CRL accessed data obtained when SaverLife members connected their bank accounts to the SaverLife platform. Anonymized transaction data included more than 14 million transactions for more than 16,000 members over an 18-month period.

CRL could see the amounts and merchants associated with those transactions. The team surfaced advances associated with five EWA providers, matching each advance to a repayment to understand the cost and frequency. Access to overdraft transactions allowed the team to probe how EWAs work with other financial products.

The team complemented its quantitative research with a qualitative component in which 18 regular users of EWA products answered questions about their use and decision-making.

The report established that the average APR for an advance repaid within two weeks was 367%, nearly as much as a typical payday loan (400%). Instead of using EWAs to get on the right financial track, consumers required repeated advances, with 75% of consumers taking out at least one advance on the same day or day after making a repayment.

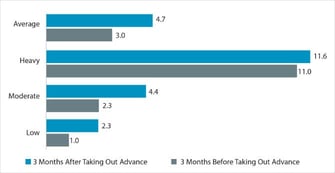

These repeated, high-interest, small-dollar loans are inordinately expensive. With many low- to moderate-income consumers already struggling to meet their expenses, the cost of EWAs made catching up and saving harder, not easier. On average, checking account overdrafts increased 56% after a consumer used a cash advance loan product.

“We’re seeing similar usage patterns with EWAs as with payday loans, where consumers get caught in a cycle of borrowing, paying, and reborrowing,” Constantine said.

Cycles of Borrowing, Repayment, and Fees

CRL’s nonpartisan work promotes financial fairness and economic opportunity for all, including families of color, rural residents, women, military personnel, low-income borrowers, low-wealth individuals, and early-career workers, according to the organization’s website.

Among many advocacy issues, it has helped lead a growing movement to cap payday loans at 36% and fought for overdraft reforms that have saved consumers more than $15 billion annually. The Center has also advocated for forbearance provisions under the pandemic-era CARES Act that have saved more than 1.1 million moderate-income borrowers from foreclosure, and it has helped lead a coalition to erase billions in student debt.

Constantine’s team was interested in better understanding EWA products after observing the industry filing bills across the country to evade credit regulations.

“Our findings around frequency of use and cost echo research produced by the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation and the U.S. Government Accountability Office,” Constantine said. “We’re concerned that the cost and frequency associated with EWAs make them counterproductive for low- and moderate-income consumers.”

The costs pile up. On average, consumers in the SaverLife data had three overdrafts in the three months before taking out an advance. The number of overdrafts increased to 4.7 in the three months after obtaining an advance.

Fees associated with the transactions create additional expenses. Most consumers surveyed paid fast-funding fees of between $0.99 and $5.99 to receive their money instantly. Those fees add up every time they take out an advance. Some companies charge fees disguised as tips, nudging consumers to offer compensation through behavioral tactics such as claiming that tips help other consumers or that they help provide healthy meals to the less fortunate.

“In many cases, consumers pay a fast-funding fee and a tip for what is ultimately a really small amount of money,” Constantine said. “That makes these advances really costly for them.”

CRL: Dedicated to Consumer Financial Protection

Companies also rely on monthly subscription or membership fees, which they charge regardless of whether the consumer takes out an advance in a given month. Those fees add to the transaction cost and are pure profit for the company.

“The biggest takeaway from our report is that EWA and cash advance products are loans and should be regulated as such,” Constantine said. “We recommend that regulators and lawmakers impose meaningful regulations on their use so that customers understand the true costs associated with taking out in advance.”

The challenge is growing. Large employers of low-income workers, such as Walmart and Target, have rolled out employer-integrated EWA products. EWAs are prevalent in the hospitality and customer service industries.

Duke University recently introduced an EWA in Durham, North Carolina, where CRL is based. Constantine said the report’s focus on direct-to-consumer EWAs makes employer-integrated products a potential subject of additional CRL research.

“They’re gaining traction across many sectors, mostly in low-wage industries,” Constantine said.

They may seem like minor costs, but they’re not. Consumers typically borrow between $40 and $100 and pay $7 per advance. When they do that repeatedly, they spend a lot on fees, which adds up for them as consumers. These costs don’t include the specific costs of overdrafts, which are typically $35.

The annual percentage rate calculation looked only at the loan fees, including membership fees, fast-funding fees, and tips. Because banks assess the overdraft fee, it was not included in the APR calculation.

“But we know it would increase the cost,” Constantine said. “The fact that consumers are overdrawing their accounts to repay these advances indicates the harm these products can cause.”