Bankruptcy is one of the most effective yet misunderstood forms of consumer protection in the legal system. Instead of jailing an individual or forcing them into indentured servitude, our legal system offers citizens a way to either escape or responsibly confront their financial obligations.

But what do you do when the very concept of bankruptcy contradicts the foundation of your beliefs? The process of resolving insolvency is a particularly tricky one for a select group of individuals — church leaders.

We spoke with Indiana University Maurer School of Law Associate Professor Pamela Foohey and discussed her latest research, “When Faith Falls Short: Bankruptcy Decisions of Churches,” to understand how clergy approach this difficult situation.

What does a church facing bankruptcy look like?

“[The ones filing for bankruptcy are] mainly small, nondenominational, Congregationalist Christian churches, so they have less of a broad governing structure,” Foohey said. “It’s more of the lead pastor, possibly in consultation with the trustee board, deciding what to do when they see that the church doesn’t have the cash flow to meet the mortgage.”

“I don’t think people know, or even think, that a church would file for bankruptcy,” Foohey said. “Or that a church might be having severe money issues that look a lot like the small businesses have, or that people have.”

George Washington University Professor of Law and Religion Robert Tuttle, who also serves as legal counsel to the Washington, D.C., Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, noted that churches part of denominations tend to have more oversight, typically in the form of a regional body, that can step in and provide financial and administrative support during times of financial difficulty.

“When they do fail, unfortunately it’s often because of a religious dispute, the moral failings of leadership (like a sexual scandal) or a terrible economic reversal in a community.”

Crystal Cathedral Ministries’ 2010 bankruptcy was one of the largest church-related bankruptcies in recent history. Upon filing, the church’s debt totaled $55 million.

But in cases where administrative intervention failed, the financial problems, “almost always involved building projects where people were over optimistic about their capacity for growth and had in mind building for the future — or that’s the story they told themselves — and convinced banks to give them loans that reflected the future value of the built property rather than the congregations present stream of giving.”

Vanderbuilt Professor of American Religious History and Presbyterian Minister James Hudnut-Beumler said church failure rates are “pretty low.”

In fact, according to Foohey’s earlier research “Bankrupting the Faith,” roughly 1 percent (around 3,200) congregations close each year.

But, “when they do fail, unfortunately it’s often because of a religious dispute, the moral failings of leadership (like a sexual scandal), or a terrible economic reversal in a community,” Hudnut-Beumler said.

How do these pastors react to bankruptcy as an option?

Half the battle, Foohey said, was making the church leaders reconcile bankruptcy with social and moral beliefs. As one of her interview subjects puts it, “I don’t think bankruptcy is a choice for the Christian” and believed bankruptcy was “the end of the world … the end of your worthiness.”

“They’re willing to do a lot, and because it’s a group investment,” Hudnut-Beumler said. “There’s always somebody or some group who’s willing to dig deeper into their resources to try to keep the thing afloat, until it’s just really impossible … because it’s unthinkable that you would let something of such religious devotion as your church fail.”

Foohey found church leaders facing serious financial problems often adopted an “ostrich defense,” wherein they ignored or refused to accept bankruptcy as an option. Leaders would “wait for divine intervention” or adopt a “build it and they will come/field of dreams” mentality.

“I don’t think bankruptcy is a choice for the Christian. [Bankruptcy is] the end of the world … the end of your worthiness.”

According to her research, church leaders began looking at bankruptcy more seriously when creditors and debt collectors started making frequent contact and initiating foreclosure procedures or other legal interventions.

Even then, she found church leaders were still reluctant to pursue bankruptcy until they discretely discussed the matter among their social networks, consulting with friends, fellow pastors and attorneys.

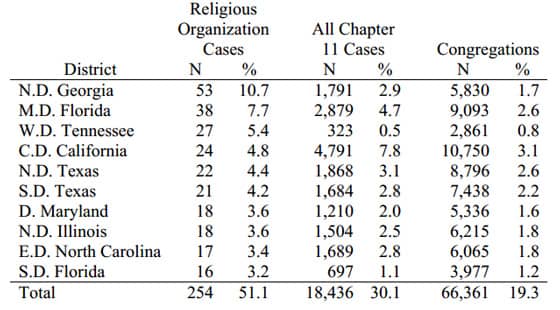

Using data from PACER, Foohey found 497 chapter 11 bankruptcies filed by 454 unique religious institutions between 2006 and 2011 — which “reflected the general makeup of religious congregations in America, with more than ninety percent of debtors affiliated with Christianity,” she wrote.

Out of the 90 federal judicial districts in which a business or organization could declare bankruptcy, just more than half (51 percent) of all chapter 11 filings occurred in 10 of them:

Of all the chapter 11 bankruptcies filed by religious institutions, 51 percent occurred in just 10 of the 90 federal court districts.

Why would 10 districts have more than half of all religious chapter 11 cases? According to Foohey, it may be that “pastors are talking to each other,” trying to confidentially gather advice and knowledge on the bankruptcy process.

“Discussions with others helped the leaders confirm the severity of their organizations’ financial situations and solidify their decisions that they had to alter their responses to their creditors if their congregations were to survive,” she wrote.

At some point during those discussions, pastors realize that despite their devotion to divinity, churches are still technically businesses and require legal solutions to their economic problems.

Leaving serious financial debts unresolved, putting the church’s property at risk of foreclosure, often convinces the indebted pastor that foreclosure is a worse fate than weathering the social stigma and shame that comes with filing for bankruptcy.

How do church leaders reconcile bankruptcy with their faith?

Despite pastors’ apprehension toward filing for bankruptcy, it turns out the bible has little, if anything, to say about the topic of bankruptcy.

“The New Testament comes together a time when the Christian church is not building large structures or taking out loans,” Tuttle said, adding that there’s “nothing I would say that bears directly on thinking about bankruptcy.”

Rather, there are only references to debt that could tangentially related to bankruptcy, such as “The wicked borrows but does not pay back” (Psalm 37:21, ESV), “It is better that you should not vow than that you should vow and not pay” (Ecclesiastes 5:5, ESV), and the more ominous “Will a man rob God?” (Malachi 3:8, NIV).

It could be that pastors, more authorities on the bible than bankruptcy codes, do not necessarily understand the dynamics of chapter 11 bankruptcy which, more often than not, results in an administrative reorganization and creation of a debt repayment schedule jointly agreed upon by the church, creditors and the courts.

“The leaders eventually saw their churches’ financial situations as legal problems and decided that chapter 11 was the best option to help them preserve the buildings and communities that their members held dear,” Foohey wrote.

Analyzing socioeconomic trends and religious reorganizations

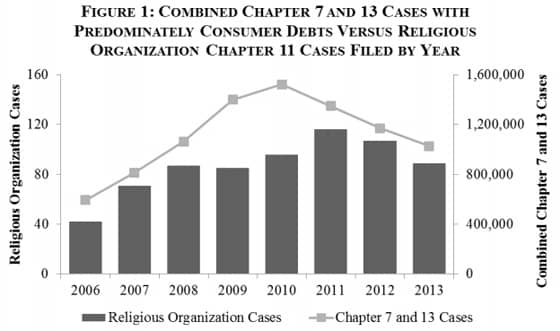

When Foohey compared the instances of chapter 7 and 13 bankruptcies (the most common for individuals and households) with religious organizations filing chapter 11, there appeared to be a correlation that, most likely, had its roots in the Great Recession.

Instances of religious organization chapter 11 bankruptcies appear to mimic cases of consumer bankruptcy filings.

“Their filings generally increased as consumer bankruptcy filings increased and decreased between 2012 and 2013 along with consumer filings,” Foohey wrote. “Indeed, their filings appear to lag behind consumer filings by one year, perhaps because consumers’ finances heavily influenced religious organizations’ financial problems.”

Televangelist Joel Osteen is often associated with the controversial “prosperity gospel.”

In late 2009, The Atlantic Correspondent Hanna Rosin made a case for a link between the mid-2000s financial crisis and a new strain of Christianity, one that appears to equate financial success with piety, in her article “”Did Christianity Cause the Crash?”

“But over the past generation, a different strain of Christian faith has proliferated — one that promises to make believers rich in the here and now,” Rosin writes. “Known as the prosperity gospel, and claiming tens of millions of adherents, it fosters risk-taking and intense material optimism. It pumped air into the housing bubble.”

“Their filings generally increased as consumer bankruptcy filings increased … perhaps because consumers’ finances heavily influenced religious organizations’ financial problems.”

However, Hudnut-Beumler advises that a majority of Christians do not adhere to the prosperity gospel, despite the fact that high-profile religious personalities such as Joel Osteen and Creflo Dollar are some of its biggest advocates.

“Maybe 10 percent or less are prosperity gospel people,” he said. “As a Presbyterian minister, I think this it is a corruption of the Christian gospel.” Indeed, even the Bible says, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25, ESV).

Foohey said there wasn’t enough evidence to make a direct link between churches’ reluctance to file for bankruptcy and the prosperity gospel.

“The pastors had a natural tendency to hope that God would provide for them in their church’s time of trouble, but these hopes were not connected to a ‘prosperity gospel’ in any way, at least in my opinion based on the interviews,” she said. “Rather, these hopes are the religious equivalent of how consumer debtors ‘stick their heads in the sand’ and hope it will all go away.”

Avoiding bankruptcy (again)

Although many pastors felt stigma and shame after filing, they found relief in their choice of rhetoric as way to psychologically and spiritually handle the bankruptcy, adopting carefully chosen terms to justify filing, Foohey’s interviews show.

“They used different terminology, referring to the filings as allowing their organizations ‘to restructure, reorganize,’ ‘to restructure, to revamp,’ and ‘to get back on track, get [back to] business as usual, straighten our mortgage, and go forward,'” she wrote. “They conceptualized their filings as ‘a temporary move,’ a ‘bridge gap,’ and a ‘transitional period’ necessary ‘to work out some kind of plan.'”

For those congregations that did survive bankruptcy, pastors typically adopted new administrative oversight, more efficient record-keeping and/or even educational programs to raise members’ financial literacy (and mostly likely the pastor’s, as well).

BadCredit.org is a secular publication that does not condemn or endorse any particular religious belief.

Image credits: says-it.com, wikimedia.org, Pamela Foohey, americapreachers.com

Advertiser Disclosure

BadCredit.org is a free online resource that offers valuable content and comparison services to users. To keep this resource 100% free for users, we receive advertising compensation from the financial products listed on this page. Along with key review factors, this compensation may impact how and where products appear on the page (including, for example, the order in which they appear). BadCredit.org does not include listings for all financial products.

Our Editorial Review Policy

Our site is committed to publishing independent, accurate content guided by strict editorial guidelines. Before articles and reviews are published on our site, they undergo a thorough review process performed by a team of independent editors and subject-matter experts to ensure the content’s accuracy, timeliness, and impartiality. Our editorial team is separate and independent of our site’s advertisers, and the opinions they express on our site are their own. To read more about our team members and their editorial backgrounds, please visit our site’s About page.