In a Nutshell: It doesn’t take a leap of imagination to understand how poor health can lead to medical debt. But a study from the nonpartisan Sycamore Institute suggests the relationship also works in reverse. Deputy Director Mandy Spears found in her research that debt tends to worsen financial well-being and discourage positive behavioral and environmental patterns. Financially challenged patients are more likely to avoid a health and debt spiral when care systems can ameliorate the corrosive effects of medical debt.

Researchers have known for some time that a person’s social factors and their health are interconnected. For example, someone’s education level, employment, income, and social support may exacerbate negative health behaviors related to diet, physical activity, and substance use.

Lack of access to a clean and safe living environment may discourage people from engaging in physical activity and increase the chronic effects of pollution and stress. Lack of high-quality healthcare can worsen poor health. Poverty and unemployment negatively affect a person’s standard of living and access to health care and may cause adverse health behaviors to worsen.

The burden of medical debt has an exponentially negative effect on the financial status of vulnerable health consumers. Medical debt often arises unexpectedly from factors beyond a person’s control. While paying off a credit card can increase a person’s credit score, paying medical debt has no financial benefit. And medical debt is frequently so high that even trying to pay it off may seem futile.

For Mandy Spears, Deputy Director of the independent public policy research center at the Sycamore Institute, the question was how much those dynamics influenced each other. In “How Medical Debt Affects Health,” Spears convincingly shows that medical debt, in and of itself, can drive poorer health outcomes.

The implication is a health and debt spiral: Poor health causes medical debt, which worsens health — and so on.

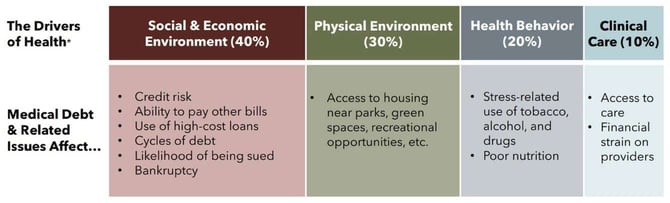

“Our job was to ask good questions and think broadly about how medical debt can impact a person’s life and how those relate to socioeconomic environment, physical environment, health behaviors, and access to clinical care,” Spears said. “If medical debt worsens health drivers, and worsened health drivers lead to poorer health, there’s a logical framework to believe medical debt influences health through social determinants.”

A Nonpartisan Approach to Policy Analysis

The nonpartisan Sycamore Institute is ideally positioned to deliver these findings. The Institute focuses exclusively on issues important to its home state of Tennessee and doesn’t take positions on policy issues or engage in advocacy or lobbying. Even its staff is bipartisan.

“We joke that we couldn’t take a position on something if we wanted to because we couldn’t possibly agree,” Spears said.

Instead of concerning itself with advocacy, the Sycamore Institute aims for a data-driven approach to discuss trade-offs between policy options. By design, its purpose is to help policymakers, community leaders, the informed public, and the media understand and address Tennessee’s significant challenges.

Sometimes, that means problem definition — understanding what’s happening in the state. The Sycamore Institute looks at theoretical policy options to address problems and at positions within the policymaking sphere to get a handle on their implications.

“The foundation’s grantees needed information people on both sides of the aisle could trust,” Spears said. “We have to be a resource for everybody, regardless of their level of expertise or political perspective.”

An example of how that works in a non-healthcare-related field concerns the Institute’s work in the politically fraught field of K-12 education, where partisan passions run deep.

Tennessee policymakers included the Institute in a legislative workgroup that looked at federal education funding in Tennessee to determine whether the financing posed unnecessary constraints on the state.

“Aside from a national organization, the National Conference of State Legislatures, we were the only group they brought in to testify that was not a state or federal agency,” Spears said. “The lawmakers valued our perspective because we were conversant on the issue and understood the trade-offs and considerations.”

Medical Debt and the Social Determinants of Health

That approach extends the Sycamore Institute’s work beyond Tennessee’s borders. Although the numbers behind the health and debt dynamic in Spears’ state may be unique, the same relationships exist everywhere.

Spears’ work in “How Medical Debt Affects Health” starts with the commonsense notion that people with medical debt tend to be in worse health. The more medical needs people have, the more likely they’ll end up with a bill they can’t afford. Once you have a bill you can’t pay, you’re less likely to return to the same hospital or doctor because you already owe them money.

The random nature of medical debt increases the stress associated with it. A car or mortgage payment may cause anxiety and damage a person’s financial status, but people choose to purchase cars and homes. Situations leading to medical debt can crop up suddenly, and there’s little price transparency associated with health care. Sometimes, medical debt arises simply because a doctor and a health insurance company disagree.

“That’s not on you — that’s not your fault,” Spears said. “But it does end up being your responsibility at the end of the day.”

The next step was understanding how the stress and financial damage caused by medical debt drive the social determinants of health. Among other things, Spears analyzed the peer-reviewed literature to document how financial stress creates a desire to find relief from that stress through the use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs.

Once a person enters a situation where they can’t afford one bill, it can snowball into longer-term financial and economic immobility. That has downstream effects on their ability to secure safe and stable housing, afford healthy foods, and maintain health insurance.

People in that position may lose access to healthy living conditions with nearby health providers and safe parks to do healthy things outdoors.

“Those are the most extreme examples of medical debt, but one bill can send a person without resources into a spiral of financial insecurity,” Spears said.

Policy Options and the Problem of Medical Debt

“How Medical Debt Affects Health” is not the Sycamore Institute’s first word on medical debt. Its work on the subject extends to a series of publications, including an analysis of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, a look at medical debt in Tennessee counties, and an examination of the distribution of medical debt among the state’s population.

There’s also a look at how a medical bill becomes medical debt and a discussion of medical debt policy options in the state.

The Institute’s even-handed approach comes to the fore in that last article, with Spears suggesting that “no single policy change would address every troubling aspect of medical debt in Tennessee and its downstream effects.”

The paper proposes upstream, midstream, and downstream policy changes to lessen the burden of medical debt. Upstream levers to prevent medical debt include ending surprise billing, extending health insurance coverage, and reducing out-of-pocket health insurance costs.

Midstream levers to manage debt include reforming provider billing and collection practices, facilitating and incentivizing personal savings, increasing access to affordable, small-dollar loans, and improving access to financial education.

Downstream levers to mitigate debt include reforming debt collection practices and lawsuits, providing greater oversight of debt settlement services, limiting how medical debt affects a person’s credit history, and even paying off debts directly.

Recent federal legislation has lessened some of the effects of surprise billing in Tennessee. The Institute has documented little policy change at the state level since it published “How Medical Debt Affects Health” in 2021.

But Spears notes that health and hospital systems are beginning to change their approaches to the issue. For example, a county court recently implemented an online pilot program to resolve unpaid bills before they land in the courtroom by working out payment plans and determining whether people are eligible for charity care.

“If it goes well, other court systems and hospital systems across the state may try to do something similar,” Spears said.