In a Nutshell: The mission of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Homeless Programs Office is to help veterans and their families obtain permanent and sustainable housing, high-quality health care, and supportive services. The office’s creative use of COVID-19 pandemic funding helped decrease the number of veterans experiencing homelessness by more than 11% since 2020. These results establish the Homeless Programs Office as a strategic model for ending homelessness in the US.

Military veterans and families are on the front lines of America’s commitment to national security and global stability. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) serves and honors veterans through its commitment to provide health care and benefits to those in need.

Unfortunately, many veterans and families experience housing insecurity and homelessness. As part of the VA’s Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Homeless Programs Office develops programs designed to end America’s veteran homelessness crisis.

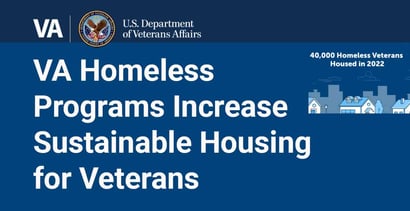

Since 2010, the VA has helped reduce veteran homelessness by more than 53%. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Homeless Programs Office took a fresh look at its operations and found new ways to partner with governmental agencies and private-sector organizations.

Since 2020, the department has received $971 million allocated through the Trump administration’s CARES Act for COVID-19 relief, and it has benefited from additional support received through the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan. Those funds have helped the VA Homeless Programs Office build new administrative flexibility into its approach to veteran homelessness.

The result is a decrease in veteran homelessness by more than 11% since 2020, with more than 40,000 veterans placed in permanent housing in 2022. Thanks to the creativity and dedication of the Homeless Programs Office, the VA has taken significant strides toward its goal of permanently preventing and ending homelessness among veterans and established itself as a model for addressing the challenge of homelessness in general in the US.

“When the pandemic hit, we recognized we needed to come together as one team with our federal, state, and local partners,” said Jill Albanese, Director of Clinical Operations and Senior Advisor for VHA Homeless Programs. “It’s one of the big reasons we were able to get so many veterans housed.”

Supportive Services Facilitate Rapid Rehousing

The VA operates a confidential Crisis Support Line to connect all US veterans and their loved ones to local resources and support. VA operates a National Call Center for Homeless Veterans to access healthcare and other services that address veteran homelessness and housing insecurity.

Calling the National Call Center at 1-877-424-3838 puts at-risk veterans, family members, friends, and supporters in touch with trained counselors who are ready to talk confidentially on a 24/7 basis.

Meanwhile, more than $700 million in CARES funding went toward the Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) program, which aims to improve housing stability for low-income veteran families through rapid rehousing and homelessness prevention initiatives. In several ways, SSVF served as a touchstone for rethinking the VA’s approach to veteran homelessness during the pandemic.

First, by building more flexibility into its internal policies, the Homeless Programs Office developed a non-congregate sheltering system for veterans that incorporated hotel stays.

“It’s not inexpensive to put folks in hotels, so we used a portion of our CARES funds to get folks to safety,” Albanese said. “We did not want to see veterans living in tents during a pandemic.”

The idea behind the non-congregate strategy is that all human beings desire privacy and security, which is not available to homeless people living en masse in large group shelters. When the choice is between living without privacy in a crowded shelter where contracting COVID is a real possibility and living on the streets, many veterans chose the latter.

By moving at-risk homeless veterans from large, single-room shelters into hotel rooms, the office increased veteran engagement with outreach workers and generated better results.

“Veterans who had been reluctant to engage with us in the past were eager to engage when we had hotel vouchers readily and quickly available,” Albanese said.

Funds for Homelessness Prevention and Facilities

Supportive Services for Veteran Families funds also went toward rental assistance. As unemployment skyrocketed and assistance checks lagged, SSVF rental assistance kept struggling veterans and families in housing and out of harm’s way.

SSVF provided bridge funds to support veterans who could not receive housing and rental vouchers because the housing authorities responsible for delivering them shut down during the pandemic.

“We got folks off the street and into permanent housing, knowing that when the housing authorities reopened, we could get them their vouchers, and they would be able to pay their rental assistance,” Albanese said.

Another portion of CARES funds supported the Homeless Programs Office’s Grant and Per Diem Program, which issues one-time grants to remodel group living spaces into individual rooms. It made sense to fund those renovations given the clear preference for private, single-use living spaces among veterans receiving support and services from the Homeless Programs Office.

However, one of the downsides to private living space is the possibility of social isolation. To combat that, during the pandemic, the Homeless Programs Office also began issuing personal electronic devices, including cellphones and tablets, to facilitate communication between newly housed veterans and outreach workers, service providers, family members, and friends.

Phones that went to veterans temporarily housed in hotels served as a substitute for interaction with the communities on the street. And phones went to permanently housed veterans who needed ongoing case management.

Larger tablet computers also found a place in the program — the Homeless Programs Office issued tablets in incarceration settings to provide remote counseling opportunities to jailed veterans.

“It was a creative way for us not to lose track of these veterans and to provide services to them as soon as they were released, which is vitally important,” Albanese said.

The VA: Creative Solutions to the Housing Crisis

Although CARES funding was temporary, American Rescue Plan funds enabled the Homeless Programs Office to continue delivering innovation to veterans experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity.

The US Congress granted flexibilities during the pandemic that will expire when the public health emergency ends, but the VA changed other policies internally. The VA could further revise its regulations to continue some of the systems and procedures that have brought positive results.

The Shallow Subsidy intervention initiative is an example. As a facet of Supportive Services for Veteran Families, which is aimed at helping veterans and families avoid eviction, Shallow Subsidy provides funds to meet about half a typical rent payment. Limited subsidies can prevent targeted populations, such as aging veterans and veterans at risk of homelessness due to income loss, from becoming homeless in the first place.

As of late 2022, the Homeless Programs Office expanded funding for incentives to landlords who may be interested in renting to at-risk veterans and families nationwide. The Homeless Programs Office also plans to increase direct marketing to landlords who may be interested in renting to at-risk veterans and families.

After the public health emergency ends, the office stands to lose the ability to use appropriated funds to pay for food, shelter, and other items. Before the pandemic, volunteer groups made those purchases. Now, an outreach worker at the medical center can meet with a veteran, assess their immediate needs, and pull the necessary money directly.

The results speak for themselves. Financial support and programmatic flexibility have enabled the Homeless Programs Office to accelerate the downward trend in veteran homelessness.

The office is an example of how, through internal cooperation, constructive partnerships, and creative use of policy, public and private organizations with similar missions can address homelessness and housing insecurity on a broader basis.

“What we’ve implemented is working, and we want to continue,” Albanese said.