2005 was a terrible year for New Orleans — Hurricane Katrina, a category five storm and meteorological juggernaut, swept up the Gulf of Mexico and devastated cities in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

Not only did the storm kill 1,833 and displace roughly 273,000 people — it was the costliest Atlantic hurricane ever, racking up an estimated $10 billion in damages in the United States alone.

But for those who survived Katrina, the troubles didn’t end when the storm passed. In New Orleans, for example, extensive flooding damaged homes across a majority of the city, many beyond repair.

However, new research by Justin Gallagher, of Case Western Reserve University and Daniel Hartley of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, shows that many of New Orleans’ residents actually saw a significant reduction to their overall debt and only experienced minor financial setbacks.

Flood insurance and the economic recovery

As the levees broke, 85 percent of the below-sea-level city of New Orleans suffered from varying degrees of flooding. In response, the federal government began organizing disaster relief efforts.

But like most things lead by the federal government, the relief efforts were notoriously slow. Luckily, roughly two-thirds of New Orleans residents who had flood insurance were able to get a piece of a $6.7 billion in insurance claims paid out to the city in 2005.

“This money got to them pretty quickly,” Gallagher said. “In contrast, the different government assistance programs … took a year or more. Insurance really was and is a mechanism to get the money in the hands of the people that are affected more quickly.”

So homeowners with damaged houses had a decision to make with their flood insurance payouts — use it to repair their damage homes or pay off the remaining mortgage balance?

Gallagher said he and his team expected to see residents in more severely flooded areas struggle with higher financial costs and damaged credit histories following the storm. “It was almost like a no-brainer we expected to find.”

However, what they discovered surprised them.

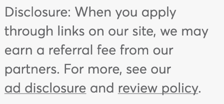

Gallagher and Hartley’s research shows a significant drop in total debt balance for many New Orleans residents following Hurricane Katrina, defying researchers’ expectations.

“We found instead there is a very immediate and sharp reduction in reported total debt held by people that were the most flooded,” he said. “So it looked like instead of accumulating more debt, which is something that we would expect in times of trouble, we saw that at a time when things were the worst, the debt actually dropped a lot.”

Pressure from mortgage lenders

“This was a puzzle for us for a little while until we ruled out all of the possible explanations except for flood insurance,” Gallagher said. “It seemed very likely that the vast majority of this reduction in debt was driven by homeowners deciding, probably while under pressure from mortgage companies, to use some or all of the flood insurance payouts to pay down off their existing mortgage debt, rather than to use it to repair their homes after the hurricane.”

Indeed, media reports show mortgage lenders began pressuring homeowners to use flood insurance money to pay down their mortgages (the claims covered as much as 92 percent of their mortgage for the most flooded areas, the research shows) instead of using it to repair their homes.

“Homeowners [decided], probably while under pressure from mortgage companies, to use some or all of the flood insurance payouts to pay down off their existing mortgage debt.”

One might think mortgage lenders would want residents to use the money to repair their homes, mitigating the reduction to property values brought on by the flooding. But lending activity following the storm tells a different story.

“We observe a much larger drop in new loans to New Orleans by non-local lenders after Katrina as compared to local lenders,” the study reads. “The immediate reduction is more than twice as large for the non-local lenders than for the local lenders whether measured in levels or percentage terms.”

The reconstruction itself may have also persuaded non-local lenders to recoup their loans — mortgage companies must monitor home repairs to avoid insurance fraud (either by the homeowner or contractors), and doing so would’ve been costly for lenders without a local presence.

Mortgages supplied by the Federal Housing Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were placed under an 11-month foreclosure moratorium (meaning homeowners couldn’t be foreclosed on due to missed payments or defaults).

However, that didn’t stop people from ultimately leaving the city in a mass exodus — the population of New Orleans dropped from 484,674 in April 2000 to 230,172 in July 2006 (right around the end of the foreclosure moratorium).

Househould finance and credit activity

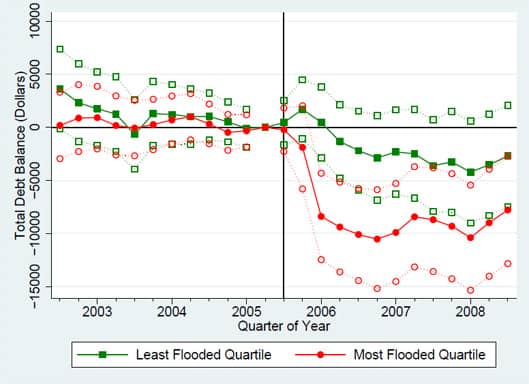

“Our expectation was that residents would use credit cards as a means to smooth the income shock caused by the flood damage and forced evacuation

of New Orleans,” the paper reads. “Surprisingly, there is only a modest change in credit card balances for either flood group after Katrina relative to the non-flooded group.”

“Surprisingly, there is only a modest change in credit card balances for either flood group after Katrina relative to the non-flooded group.”

While residents in the most flooded areas increased their credit card balances on average by $700 (a 22 percent increase over their average balance of $3200 prior to the storm), the increase was only temporary, with subsequent quarters showing statistically insignificant changes to credit card balances.

However, residents did see an average increase of $436 for automobile-related debt a year following the storm.

In terms of credit health, many residents in flooded areas saw a temporary drop in their Equifax Risk Scores™ (a credit score model similar to FICO’s) of about four to seven points. Likewise, 90-day delinquency rates rose approximately 10 percent during the same period.

Together, the figures suggest “Hurricane Katrina led to a modest and temporary decline in the financial health of the most flooded New Orleans’ residents relative to non-flooded residents,” according to the research.

Moving forward

With the expectation that climate change will increase the frequency of catastrophic weather events like Katrina, “We thought it would be very important to try to get a very detailed understanding of what happens to people after these big disasters,” Gallagher said.

Although residents did see some financial setbacks immediately following Katrina, Gallagher noted that debt levels and credit scores “returned to normal” in the two to three years following the storm, and that most indicators of financial shock had “disappeared.”

“Our takeaway is that, given the current amount of federal assistant along with flood insurance, even in an event that is very large, such as Hurricane Katrina,” he said, “The negative effect of this natural disaster peters out after two or three years, and at least according to the financial information that’s taken directly from these individuals’ financial background, there isn’t any significant drag after a few years.”

Are you worried you won’t be able to refinance a new home with bad credit? Consider contacting a subprime home loan lender today.

Advertiser Disclosure

BadCredit.org is a free online resource that offers valuable content and comparison services to users. To keep this resource 100% free for users, we receive advertising compensation from the financial products listed on this page. Along with key review factors, this compensation may impact how and where products appear on the page (including, for example, the order in which they appear). BadCredit.org does not include listings for all financial products.

Our Editorial Review Policy

Our site is committed to publishing independent, accurate content guided by strict editorial guidelines. Before articles and reviews are published on our site, they undergo a thorough review process performed by a team of independent editors and subject-matter experts to ensure the content’s accuracy, timeliness, and impartiality. Our editorial team is separate and independent of our site’s advertisers, and the opinions they express on our site are their own. To read more about our team members and their editorial backgrounds, please visit our site’s About page.