In a Nutshell: Gentrification is a sensitive topic for many Americans, yet there has been very little research done on the issue that presents rigorous data about how it impacts individuals. But one recent study, “Gentrification And The Health Of Low-Income Children In New York City,” which was conducted by a team of researchers from the NYU Furman Center and NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service dives deeper into the topic. The researchers looked at New York City neighborhoods that underwent gentrification between 2009 and 2017, and children who lived in those neighborhoods. The study did not find any significant impact on conditions such as asthma or obesity. But it did reveal a moderate increase in the rate of diagnoses for anxiety or depression among the children in the study.

Gentrification has been a point of controversy in the United States since the early 1900s. Proponents of gentrification point out that the process provides an economic boost to municipalities as businesses and more affluent citizens return to economically declining areas.

But opponents believe gentrification’s overall impact is negative. Rising property values and rents may push longtime residents out of their homes. Cities not only lose longstanding members of the community, but gentrification also eliminates an area’s unique character and culture as well.

These are the broad strokes, anyway, in which gentrification is often discussed.

But researchers at NYU recently conducted a study that looks at gentrification on a human level by exploring how it impacts children who live in areas undergoing the disruptive process.

Gentrification in U.S. cities has been a controversial topic since the early 1900s.

The results of the study were laid out in “Gentrification And The Health Of Low-Income Children In New York City,” which was recently published in Health Affairs. The article was written by the researchers, Kacie L. Dragan, who was at the time the lead analyst for the Policies for Action Research Hub in the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service; Ingrid Gould Ellen, the Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning and faculty director of the NYU Furman Center; and Sherry A. Glied, professor of public service and dean of the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University.

We recently spoke to Charles McNally, the NYU Furman Center’s Director of External Affairs, about the recent work and how it illuminates the discussion around gentrification.

“Our mission is to advance research and the debate on housing, urban affairs, and land use issues in New York City,” McNally said. “This research falls very squarely within that. We look a lot at neighborhood change and how it impacts households and families.”

He said the NYU Furman Center is constantly thinking about how its research can be relevant to policy, and how it can help inform decision-makers who are shaping how U.S. cities are growing and changing.

Defining Gentrification and Setting Up a Longitudinal Study

McNally said Ellen, a faculty director and a lead researcher on the study, has done a lot of work looking at gentrification throughout her career and brought years of expertise to the study.

“The anxiety around gentrification and what happens as neighborhoods change is really sort of catalyzing opposition to building new housing,” McNally said. “In light of that opposition, it gets hard to solve some of the housing shortages and problems that we’re trying to address.”

He said studies such as “Gentrification And The Health Of Low-Income Children In New York City” seek to bring more clarity to the issue and help the public and policy-makers hold informed opinions on the topic.

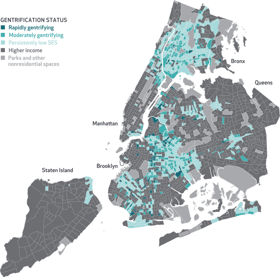

The researchers defined the parameters of their study in part by defining the parameters of what is considered a gentrifying neighborhood.

“It’s a very emotional issue. People are concerned about displacement and cultural displacement,” McNally said. “But given all that emotional investment, there’s very little rigorous data on exactly what the impacts of gentrification are on health and families.”

As the research team honed in on the subject matter they were interested in researching, they established parameters around the study.

“To distinguish gentrifying neighborhoods from neighborhoods that did not experience gentrification, the authors use the following definition: gentrifying neighborhoods in New York City (1) began the study period, 2009-2017, in the bottom 40% in terms of mean neighborhood income and, (2) between 2009 and 2015, had the greatest increases in their share of adults with college degrees,” according to the NYU Furman Center Blog.

The team used data from New York’s Medicaid program, comparing the health outcomes of children in New York City between 2009 and 2017.

The researchers compared the health outcomes of children who lived in low-income neighborhoods that underwent gentrification between 2009 and 2015 with children in similar neighborhoods that did not see gentrification in that time.

Children Growing Up in Gentrifying Neighborhoods Experienced 22% Higher Rates of Anxiety or Depression

The researchers ended up with 72,000 children in their study. They examined the incidence of obesity, asthma, attention hyperactivity disorder, anxiety or depression, and — for 2015 to 2017 — the rate of ER visits or hospitalizations and proportions of children who went to at least one well visit.

The study’s data indicated that children who experienced the gentrification of their neighborhoods did not see increased rates of asthma or obesity when compared with children in neighborhoods that were not gentrified.

But the researchers did find moderate increases in the diagnosis of anxiety or depression among children in gentrifying neighborhoods.

“Children starting out in areas that gentrified had a 22 percent higher prevalence rate than did children who started off in low-SES areas that did not gentrify,” according to the study. “The effect appears to be particularly driven by children who moved from rapidly gentrifying areas as well as by those who stayed but lived in market-rate rental housing.”

The study was conducted by Kacie L. Dragan, who was at the time the lead analyst for the Policies for Action Research Hub in the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service; Ingrid Gould Ellen, the Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning and faculty director of the NYU Furman Center; and Sherry A. Glied, professor of public service and dean of the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University.

These numbers, combined with the lack of indication that gentrification had any notable impact on asthma or obesity, led the research team to conclude that although this study did not reveal significant health impacts, it doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

“Thus, it is possible that health effects will emerge over the longer term,” according to the study. “Moreover, our findings of elevated anxiety and depression merit continued investigation as this cohort continues to age into later adolescence, when these conditions are more prevalent.”

This research presents an important starting point for future studies that may incorporate this data with a broader age range to provide a deeper exploration of this topic.

“Neighborhood environments undoubtedly play a role in children’s health, but the largely null findings in both our analysis and the MTO (Moving to Opportunity) research suggest that the relationship between neighborhood economic change and health may be more nuanced than is often assumed,” concluded the authors.

“This research suggests that really is a nuanced picture,” McNally said. “You know, it’s not all good or bad, even necessarily from the same household. Hopefully, this provides a richer picture of what gentrification means for neighborhoods in New York and other cities across the country.”

Advertiser Disclosure

BadCredit.org is a free online resource that offers valuable content and comparison services to users. To keep this resource 100% free for users, we receive advertising compensation from the financial products listed on this page. Along with key review factors, this compensation may impact how and where products appear on the page (including, for example, the order in which they appear). BadCredit.org does not include listings for all financial products.

Our Editorial Review Policy

Our site is committed to publishing independent, accurate content guided by strict editorial guidelines. Before articles and reviews are published on our site, they undergo a thorough review process performed by a team of independent editors and subject-matter experts to ensure the content’s accuracy, timeliness, and impartiality. Our editorial team is separate and independent of our site’s advertisers, and the opinions they express on our site are their own. To read more about our team members and their editorial backgrounds, please visit our site’s About page.